Martin Goldsmith never knew what happened to his parents before they escaped from Germany in 1941. Over a weekend, he confronts his father and we are brought back to the complex and confusing 1930s when the parents were young musicians.

Background

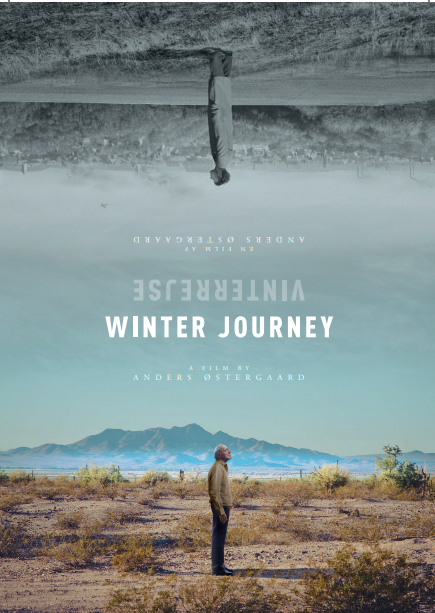

Hailed as “a masterpiece,” “a miracle,” “exhilarating,” and “sublime” by critics in Europe, and “haunting” and “phenomenal” by The Hollywood Insider, Winter Journey is both a highly personal meditation on fate and a fascinating exploration of a little-known aspect of the Nazi era of German history. Directed by Academy Award-nominated Danish filmmaker Anders Ostergaard, Winter Journey also stands as the final film in the storied career of the great Swiss actor Bruno Ganz. Best known for starring in Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire and The American Friend and his stunning portrayal of Adolf Hitler in Downfall, here Ganz plays George Goldsmith, a retired musician and furniture salesman with a closely-guarded secret. Once again quoting The Hollywood Insider, Ganz’s performance in WJ is “a perfect distillation of the actor’s distinguished career and a fitting epilogue.”

George Goldsmith, nee Guenther Ludwig Goldschmidt, met his future wife, Rosemarie Gumpert, when they were both members of the Judische Kulturbund, or Jewish Cultural Association, a remarkable ensemble of Jewish musicians, actors, and dancers that was maintained as an insidious propaganda tool by Minister Joseph Goebbels. Guenther and Rosemarie performed with the Kulturbund orchestra between 1935 and 1941. Now living at the edge of the Arizona desert in Tucson, the elder Goldsmith shares his recollections of his tumultuous youth in a series of conversations with his son, Martin Goldsmith, who appears throughout the film but never on camera. Martin, known to American radio listeners as the long-time host of NPR’s “Performance Today” and the host of the PBS special “Classical Rewind,” used those conversations as the basis for his acclaimed book The Inextinguishable Symphony, which in turn inspired Winter Journey. Ostergaard weaves those conversations together with archival footage and ingenious green-screen recreations of actual events into a journey through time and space that leads inexorably to “the film’s gut-punch of a finale.” (HI) Dealing with themes of guilt, Jewish identity, the father/son dynamic, and the responsibilities of the Second Generation, Winter Journey is moving proof of William Faulkner’s timeless observation that “the past is never dead; it isn’t even past.”

Artistic Statement

The story of the Jüdische Kulturbund offers an intriguing insight into the early – and less known – stage of Nazi rule, where schemes for mass deportation, let alone genocide, had not yet even been developed. Instead, the regime experimented with an apartheid approach where Jews and non-Jews were to co-exist in a racial hierarchy. Many Jewish Germans co-operated – partly out of submissive tradition, partly in the secret hope that Hitler would soon disappear and their civil rights would be restored. In all its complexity,

it is thought-provoking to see the Kulturbund promoting itself proudly in the midst of Nazi Germany “like it was some kind of Hitlerjugend” – as the character Martin says in the film.

But just as unique are the opportunities offered by the way the story is told. The whole film is laid out as a son’s investigation of his father’s past and this soon leads us to the issues of survivor’s guilt and to the repercussions of the Holocaust in the next generations. Especially the latter remains a burning issue – even in generations much younger than our protagonists. Living in Berlin and travelling widely in Central Europe, I am constantly reminded that the wounds are still not healed and that they will need artistic treatment for many years to come.

Over the years, a particular image of the Holocaust has come to dominate our collective imagination. It is that of the tall, blond SS officer chasing a crumbling little in Orthodox clothing down some ghetto street in Poland or Russia. These are becoming cultural and racial stereotypes that I would like to refine by looking at the largely secular and highly assimilated German Jews.

Actually, we should maybe call them the Jewish Germans. They lived standard German lives complete with Christmas trees, Sunday dinners and a Richard Wagner bust on the piano. They looked at themselves as part of the mainstream – being Germany as much as anybody else. And this only deepens the tragedy. More than a clash between alienated tribes, the persecution of the German Jews was a grusesome family affair, a fratricide that has left modern Germany in a permanent state of self-amputation.

When George, the old emigré, insists to be German and refuses to be a Jew, he is losing a battle against his investigative son. His position seems irrational, even awkwardly anti-Semitic. But he is a man in mourning over Germany as a home and as a lost civilization where – in his eyes – there once was a brotherhood of man, free of ethnic categories. This portrayal of the cultural loss – besides of all the immediate suffering – is what this film in particular can offer to the Holocaust discourse.

I have always had an eclectic film language, mixing many narrative methods to create a cinematic journey in the borderland between drama and documentary. This project is no different.

The basis of the film are the conversations between father and son in Tucson, Arizona. This will be a full drama production with actors, props and a scripted dialogue, albeit based on real events. The feel, however, will be somewhat documentary since the son is running a camera and stays out of the picture while interviewing his father.

Whenever we travel back to Germany of the 30s and 40s, we apply a very different language – namely sequences of recreated still images. They could be perceived as snapshots of the events discussed and we may use historical cameras to give the lensing a period feel.

The still-photo aesthetic intrigues me as a way to create the distance of memory, mimicking the way we all tend to recall events in moments of significance. It also draws on my documentary experience where I had often discovered the surprisingly cinematic quality of stills in sequence.

As the film progresses I will start projecting our reenacted charachters onto an authentic background from archive photos making use of green-screen technique. This is a more playful development of the style where I also may allow the characters to move around in live images. At the moment we are testing this method as it applies to scene 14 – Günther’s journey through Germany during the Kristallnacht. In this exercise, we are deliberately letting our protagonist move around in well-known pictures of the broken shop windows as we look for a new perspective to these historical icons.

A third method is the application of dialogue and sound effects to existing archive film from the period. It is not a style that can carry long stretches of narrative, but it can offer the right period accents and be an icing of the cake. I tried out the method in my previous production, “1989” with convincing results.

Also, I am always looking out for interesting comments coming from other sources – such as the several quotes from a stage production of “The Magic Flute”.

I have previously been surprised to see how effortlessly diverse elements can flow together if there is absolute clarity about the story and the dramatic purpose of each scene.

Festivals, Screenings, & Awards

IDFA: International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam

CPH:Dox Film Festival

Haida International Film Festival

UK Jewish Film Festival